LI Pulse: Confessions of a Mortgage Predator

April 1, 2009

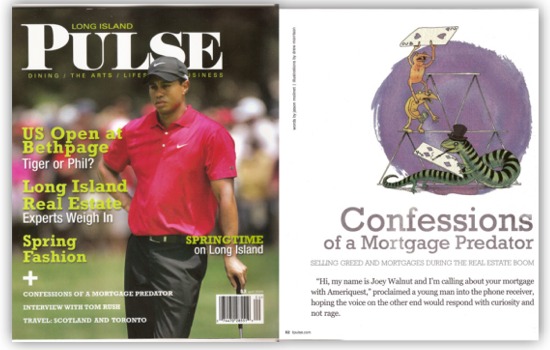

Title: Confessions of a Mortgage Predator; Selling greed and mortgages during the real estate boom

Publication: Long Island Pulse magazine

Author: Jason Molinet

Date: April 2009

Start Page: 62

Word Count: 1,642

“Hi, my name is Joey Walnut and I’m calling about your mortgage with Ameriquest,’’ proclaimed a young man into the phone receiver, hoping the voice on the other end would respond with curiosity and not rage.

In a white-washed office space in a non-descript strip plaza off a traffic-choked artery in Nassau County, Joey begins each cold call in similar fashion. A swig of Vodka-spiked Pepsi between prospects takes the edge off. He repeats the process more than 100 times each evening, following a list of random leads and reading off a tight script.

“It’s really not an easy job to call people at their house at night,’’ said Joey, a college grad. “It really isn’t. So a few drinks would loosen you up. And some people would do coke because it makes you go insane and you’d pound away at the phone.’’

Think Jim Cramer insane. And the goal was mad money.

The payoff comes six to eight weeks later when leads turn into closings and his company collects up to 10 percent of the loan when all the fees are tallied. That’s a $30,000 chunk of gold on a $300,000 mortgage. Everyone gets a piece of the pie, right on down to a cool $5,000 windfall for so-called loan officers like Joey.

These cocaine cold-callers were living the high life, indeed.

Joey — his name has been changed to protect his identity – worked at various mortgage brokerages for three years beginning in late 2004. And while his story may not reflect the industry as a whole, it is emblematic of a decade-long real estate boom that turned homes into ATM machines and saw greed swell to towering heights.

“I was amazed at how many people were involved in the loan and knew this wasn’t helping the situation for the person,’’ said Joey, who is still in sales but got out of real estate in 2007. “Bank reps. The bank taking on the loan. Brokers. Underwriters. Lawyers. The title company. There’s just a lot of people getting paid on each loan.’’

Buy a new car. Consolidate debt. Take an extravagant vacation. A lower monthly payment. There were a million reasons why homeowners looked to refinance. The nexus of rising home values, low interest rates and loose banking practices spawned the great mortgage grab. Long Island, home to mortgage heavyweight American Home Mortgage Investment Corp. and in the shadow of the world’s financial hub, proved to be fertile ground for brokers.

All of which made the subsequent housing collapse all the more spectacular. American Home, the region’s sixth-largest employer, imploded in August 2007. Mortgage companies were the first to suffer as home values leveled off and lending guidelines tightened. The misery spread quickly.

Twenty-five banks nationwide have been shut down by federal regulators and 2.22 million homes sank into foreclosure a year ago, according to Hope Now Alliance. The Standard & Poor’s/Case-Shiller U.S. national home price index recorded an 18 percent drop in home values in the fourth quarter of 2008.

While New York hasn’t been as hard-hit as Arizona, California or Florida, the sting can be felt on every corner of Long Island as the real estate bubble gave way to a wider recession. The housing market alone has amassed some grim statistics. Suffolk endured 5,855 foreclosures last year, according to RealtyTrac, the fourth-highest in the state. Nassau saw 4,099 foreclosures a year ago.

“Banks and brokers created the problem. It’s not the borrower’s fault,’’ said Syosset-based attorney James G. Preston, who oversaw 30 closings a week at the peak in 2004. “They sucked these people in.

“If you look at the people selling this stuff they’re kids — young men and women just out of college. It’s like selling stock. They were motivated by money. They were quintessential sales men. Give them a product and let them go.’’

Looking back, the housing bubble was hard to miss. There were legitimate people such as Preston earning a living on the gold rush and prospectors such as Joey panning for riches with the backing of dubious operators.

Some mortgage brokers struck it rich. But especially banks, which played the ultimate game of zero accountability. They outsourced their sales force to mortgage brokerages and then spun off the loans to Wall Street as mortgage-backed securities, raking in a percentage off each transaction – all without consequence.

“One of the real problems is the disconnect between the person selling the loan and the people who owned the loan,’’ said Preston, whose business has gone from 90 percent real estate to just 10.

Banks needed to show sales growth. But when you’ve already leant to everyone with good credit, what do you do next? You create financial products for everyone else. The result fed the rise of mortgage brokers and forced anyone who owned a home to fend off nightly calls – and the temptation — to refinance.

Joey was lured to the mortgage game by the friend of a friend, who bragged of $250,000 paydays and backed it up by driving a red Ferrari.

He started as a cold caller and graduated to loan officer within three months. All while working in an office space straight from a Hollywood script — a large vacuum with folding tables, phones and chairs and little else. This is the pit where newbies as young as 18 earned their stripes as cold callers who made more than 100 phone calls a night looking for leads. At least 97 percent of those never amounted to anything more than voice mail or irate hang-ups.

“Some people drank and some people did drugs,’’ Joey said. “It was out in the open. It was like nothing. My boss said, ‘If you have to do coke to make money, then do coke.’ That was the mindset.’’

The point was to relentlessly pursue the next lead. The cubicles off to the sides were staffed by loan officers, who armed with someone’s credit history, shopped potential customers to banks in search of favorable rates. Shadowy managers lurked in offices at the back, pushing everyone to do whatever it took to close.

“It was a shitty version of ‘Boiler Room.’ Just nowhere near as much money,’’ Joey said. “We’d go into the meeting room and the boss would say, ‘Do I have to throw my fucking keys on the table?’ He’d throw the keys to his Beamer and then the keys to his house. Just like ‘Boiler Room.’ ‘Is this what I have to do to get you guys to work?’”

Closing meant using tactics that bordered on illegal. Initial meetings were marked by blank pages in place of good faith estimates, which were supposed to disclose all closing costs. Inflating incomes of borrowers for what are called stated income loans was not uncommon. Few mortgage companies operated this far out on the edge. Joey happened to break in at one with all the cred of a pro wrestler.

They targeted mostly working class minorities in Nassau, Suffolk and Queens. And they pushed the most profitable mortgages, such as the crippling MTA loan.

“This loan killed people,’’ Joey said. “The real interest rate was 7.5 percent. But they only paid one percent interest. The rest – 6.5 percent – would get added on to their loan balance. So if the real amount they owed was $1,500, they would only pay $1,000. The extra $500 would get added to the loan. They weren’t paying down the house and the loan amount was going up every month.’’

In the end, this loan also helped kill off the once-lucrative mortgage industry.

“Obviously, there were a lot of people out there pushing that because of lot of people are in trouble today,’’ said Peter J. Elkowitz, president of the Hauppauge-based Long Island Housing Partnership, a non-profit which helps negotiate better terms for struggling homeowners.

Don’t blame Joey, who got close to clients and gave them his cell phone number. It was the system that was corrupt. Joey tried to be genuine through the entire process – up to the point of disclosing the true extent of closing costs. This was a strange dance brokers engaged in with homeowners.

Many clients knew what they were in for. They had refinanced before and came back for more. Such was the magic of rising home values. Take the case of a truck driver from East Islip who regularly checked in on the status of his loan.

“He called up drunk once and said, ‘I need this money so bad.’ I think he had a gambling debt,’’ Joey said. “When we got to the closing he didn’t care about the fees. We charged people so much money. But in many cases they are taking out $50,000. All they are thinking about in their head was, ‘I’m going to get a check for $50,000.’’’

It would be easy to shake an angry fist at predatory loan brokers. Or point a finger at the banks, which have bankrupted countless families while siphoning off bailout money at the expense of us all. But when “Greed is good,’’ is co-opted as the mantra of an entire generation, you know the root cause of the real estate bubble is much deeper and complex than anyone is willing to admit.

One thing everyone can agree on is the great cash grab is over. Everyone somehow feels dirtier for it. Even the cocaine cowboys who put homeowners into loans they couldn’t afford — they internalize the guilt while offering up Suzie Orman-like insight.

“The fault lies with everyone,’’ Joey concludes. “There were so many people involved. It wasn’t just us. The banks were approving these loans. The lawyers were closing these loans. The people who we were refinancing knew they were going to get an adjustable rate and that it would adjust in two years. Everybody had their own reason to do what they were doing.’’